From BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 479, May 28, 2017, by Dr. Max Singer*:

Israel is not facing a dilemma about how much, if any, land to give up from the West Bank, because the Palestinians will not agree to take land and cannot be forced to do so.

The Palestinian community sees peace with Israel as defeat in their 100-year struggle. Continued Israeli occupation is one of the Palestinians’ best weapons against Israel, and they will not give it up while their war to eliminate Israel continues.

Israelis should recognize that since the Palestinians are forcing Israel to continue the temporary but long-term occupation, Israelis need to

- cooperate in reducing the moral and other costs of that occupation; and

- stop telling the world that Israel could choose to end the occupation.

The occupation, like the need for military strength and to absorb casualties, is part of the price Israel has to pay to live here. Maturity means being able to go forward with no solution in sight.

Ehud Barak recently had a long review in Haaretz of Micah Goodman’s important new book, Catch 67, to which Goodman responded the following week. Goodman argues that Israel’s 1967 victory created a “catch” or trap reflected in Israel’s current dilemma, in which both sides (the Israeli political left and right) are correct. Barak disagrees. In his view, the choice is clear: the left is correct.

Both Barak’s own view and his telling of Goodman’s ignore the reality of Israel’s actual choices today. We are not facing a dilemma about giving up territory. We are facing a distasteful task, and a need for patience over a period of decades.

Israel does not now have a choice about giving the Palestinians land or creating a Palestinian state; Israel is therefore not facing a dilemma.

While there are undoubtedly peace-seeking Palestinians, as a community, the Palestinians have not even begun to discuss the possibility of making a peace that accepts Israel and ends the Palestinian effort to gain all the land “from the river to the sea.” Nor have they begun public discussion of the possibility of most of the “refugees” settling outside Israel. Without debate among Palestinians, there is no way they can give up their determination to destroy Israel and make a genuine peace.

There is zero chance that there could be a real peace agreement now regardless of how much land Israel would be willing to give up.. A true two-state solution would finally defeat Palestinian and Arab efforts of a century, and they are not yet ready to accept defeat. Whatever disagreement there is among Israelis about how much land, if any, Israel should give up to get peace, that disagreement is not what is standing in the way of peace.

Theoretically, there are two other possibilities that might create a dilemma for Israel about giving up land. The first would be an agreement with the Palestinians to take over some of Judea and Samaria without making a full peace with Israel. The second would be a unilateral action by Israel to separate the peoples and end the occupation without Palestinian agreement.

For the reasons discussed below, neither of these is a realistic possibility regardless of how much of Judea and Samaria Israel is willing to give up. Again, no real dilemma.

The Palestinians have a voice in what happens. The choice they have made is to force Israel to “occupy” them, because they want to keep up the struggle to destroy Israel. Being a victim, an “occupied people,” improves their diplomatic position, causes Israel pain, and provokes internal conflict within Israel. These effects are bad for Israel and good for the Palestinians. Indeed, the more harmful they are for Israel, the more desirable they are for the Palestinians.

There would have to be a lot more disadvantages to the status quo for the Palestinians before they would give up such a weapon against Israel to improve their living conditions. This is especially true for the Palestinian leadership, which suffers less from the status quo than most Palestinians and benefits more from the continuation of the conflict.

But if the Palestinians will not make an agreement that would sacrifice the advantage of forcing Israel to be an “occupier”, is there any way that Israel can force them to do so by taking unilateral action to separate the peoples? This idea appealed to Sharon, and so he organized Israel’s “disengagement” from Gaza. Some Israelis say the withdrawal was a good idea that only worked out badly because it was done unilaterally. But why should we think the Palestinians would have agreed to arrangements that would have been better for Israel? They consider themselves to be at war with us. They want to cause us pain and put us at a disadvantage, and are willing to accept casualties and suffering to do so.

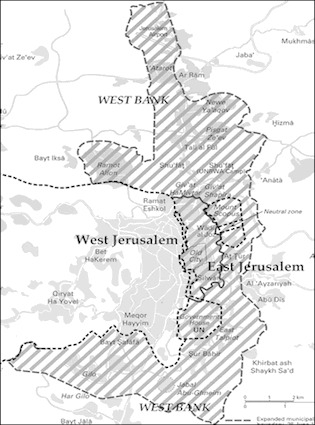

Gaza was simple, but the West Bank is complicated. There is no way Israel can separate itself from the Palestinian population in the West Bank without Palestinian agreement. This is because of Israel’s military need for access to the Jordan Valley, which would be true even if there were no settlement blocs.

Even if all the ideological settlements and hilltop outposts were gone, no unilateral Israeli withdrawal could produce a stable new status quo that we could impose on the Palestinians. Also, Israel is still regarded internationally as occupying Gaza even though it has withdrawn completely. The same would be true for Judea and Samaria after an Israeli unilateral withdrawal. The Palestinians would insist that they are still occupied and would take steps to force Israel to act in the evacuated areas.

So the Palestinians have us trapped. Although we have committed ourselves to the principle that the occupation in Judea and Samaria is temporary, we will be stuck with it for a long time. We also have to continue taking casualties and sending our children to become soldiers and to kill people. We were not given our home on a silver platter.

This reality means that the question of what land we should give up is a question for the fairly distant future. When there is a real possibility for improving things by giving up land, conditions in our region and perhaps the world will be unpredictably different than they are today. Our disagreements over how much land, if any, to give up make no difference right now. We are not facing a practical dilemma. There is no reason we should continue to beat up each other about what land, if any, we should be willing to give up for what benefits.

A solid majority of Israelis and our government have decided that Israel should be willing to give up most of Judea and Samaria in order to have peace, and perhaps even to separate ourselves from the Palestinians without peace. An even bigger majority is opposed to any withdrawals while the Palestinian community is in its current state. Therefore it is not true that our conflict with the Palestinians is the result of a stubborn or selfish insistence on holding onto all of the land of Israel. But there is nothing we can do at present to implement our willingness to give up most of the West Bank.

What can we do to make things better while we are living with the status quo? First, if we recognize that the Palestinians will not give us any way of getting out of being “occupiers,” we can work together, left and right, to reduce the moral and other harm of the “occupation.” And we can stop the internal name-calling and harsh charges against each other for not trying hard enough to end the occupation. We shouldn’t be fighting over something we have no power to change. The energy used for such fights should be directed towards making the occupation less harmful.

Our diplomatic position would also improve if there were fewer Israelis blaming one another for the continued occupation when Israel has no choice in the matter.

For the longer term, we should do whatever we can to make the Palestinians and the Arab world more willing to give up their determination to destroy us. Being nicer to them might help, although that is not usually a very effective strategy in the Middle East. It may be more useful to let them see that we are not riven by internal division or unable to bear the moral burden of being occupiers, so we are as willing as they are to continue living with the status quo indefinitely. The US could help by replacing false “even-handedness” with a truth-telling strategy that shows the Arab world that the US will not help them destroy Israel.

Many Israelis argue that we have to find a solution for our conflict with the Palestinians, and some insist that the problem is urgent (“Peace Now.”) But the experience of Israel’s first sixty years should teach us that patience is an advantage and perhaps even a necessity. What entitles us to have a solution available?

This is not to argue that the status quo does not have dangers. Israel is not safe. We are strong but also vulnerable, and quite capable of making decisive mistakes. But eagerness to settle our conflict with the Palestinians will not make us safe. Neither will anything else. Keeping our home here requires that we accept dangers and human costs of all kinds.

*Dr Singer, a founder and senior fellow of the Hudson Institute, is a senior fellow at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University in Israel.

*Dr Singer, a founder and senior fellow of the Hudson Institute, is a senior fellow at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University in Israel.