As jihadist lawlessness blazes from central Africa to the Middle East, the alliance between the US and Saudi Arabia is a last reminder of an order in which national interest trumped ideology. Henry Kissinger explores what the West must do to put out the fires

In the spring of 1947 Hassan al-Banna, an Egyptian watchmaker, schoolteacher and widely read self-taught religious activist, addressed a critique of Egyptian institutions to King Farouk. It offered an Islamic alternative to the secular state.

In studiedly polite yet sweeping language al-Banna outlined the principles and aspirations of the Egyptian Society of Muslim Brothers (known colloquially as the Muslim Brotherhood), the organisation he had founded in 1928 to combat what he saw as the degrading effects of foreign influence and secular ways of life.

The West, al-Banna asserted, “which was brilliant by virtue of its scientific perfection for a long time . . . is now bankrupt and in decline. Its foundations are crumbling and its institutions and guiding principles are falling apart.” Though he did not use the terms, al-Banna was arguing that what is known as the “Westphalian” world order had lost both its legitimacy and its power.

No truly global “world order” has ever existed. What passes for order in our time was devised nearly 400 years ago at a peace conference in the German region of Westphalia after a century of conflict across central Europe. It relied on a system of independent states refraining from interference in one another’s domestic affairs and checking one another’s ambitions through an equilibrium of power.

The Westphalian system spread round the world as the framework for a state-based international order spanning multiple civilisations and regions, because as the European nations expanded they carried its blueprint with them. Al-Banna was announcing that the opportunity to create a new world order based on Islam had arrived.

If a society were to dedicate itself to a “complete and all-encompassing” course of restoring the original principles of Islam and building the social order that the Koran prescribed, the “Islamic nation in its entirety” — that is, all Muslims globally — “will support us”. “Arab unity” and eventually “Islamic unity” would result.

A true Muslim’s loyalty, al-Banna argued, was to multiple, overlapping spheres under a unified Islamic system whose purview would eventually take in “the entire world”.

Towards non-Muslims, as long as they did not oppose the movement and paid it adequate respect, the early Muslim Brotherhood counselled “protection, moderation and deep-rooted equity”.

Assassinated in 1949, al-Banna was not vouchsafed time to explain in detail how to reconcile the revolutionary ambition of his project of world transformation with the principles of tolerance and cross-civilisational amity that he espoused.

The record of many Islamist thinkers and movements since then has resolved these ambiguities in favour of a fundamental rejection of religious pluralism and secular international order.

In 1964 the religious scholar and Muslim Brotherhood ideologist Sayyid Qutb articulated a declaration of war against the existing world order that became a foundational text of modern Islamism.

In Qutb’s view Islam was a universal system offering the only true form of freedom: freedom from governance by other men, manmade doctrines or “low associations based on race and colour, language and country, regional and national interests” (that is, all other modern forms of governance and loyalty and some of the building blocks of the Westphalian order).

Islam’s modern mission, in Qutb’s view, was to overthrow them all and replace them with what he took to be a literal, eventually global implementation of the Koran. As with all utopian projects, extreme measures would be required to implement it. While most of his contemporaries recoiled from the violent methods he advocated, a core of committed followers began to form.

To a globalised, largely secular world judging itself to have transcended the ideological clashes of “history”, the views of Qutb and his followers appeared so extreme as to merit no serious attention. Yet for Islamic fundamentalists these views represent truths overriding the rules and norms of international order.

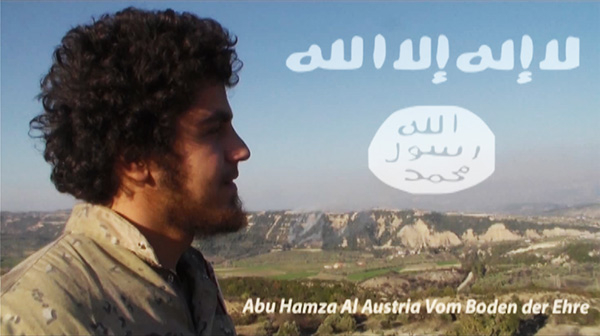

They have been the rallying cry of radicals and jihadists in the Middle East and beyond for decades — echoed by al-Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, the Taliban, Iran’s clerical regime, Hizb ut-Tahrir (the Party of Liberation, active in the West and openly advocating the re-establishment of the caliphate in a world dominated by Islam), Nigeria’s Boko Haram, Syria’s extremist militia Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (Isis), which launched a big military assault this year.

Purity, not stability, is the guiding principle of this conception of world order. In the purist version of Islamism the state cannot be the point of departure for an international system, because states are secular and hence illegitimate; at best they may achieve a kind of provisional status en route to a religious entity on a larger scale. Non-interference in other countries’ domestic affairs cannot serve as a governing principle, because national loyalties represent deviations from the true faith and because jihadists have a duty to transform the world of unbelievers.

For a fleeting moment the Arab Spring that began in late 2010 raised hopes that the region’s contending forces of autocracy and jihad had been made irrelevant by a new wave of reform.

The Arab Spring started as a new generation’s uprising for liberal democracy. It was soon shouldered aside, disrupted or crushed. Exhilaration turned into paralysis. The existing political forces, embedded in the military and in religion in the countryside, proved stronger and better organised than the middle-class element demonstrating for democratic principles in Tahrir Square.

As a military regime has again been established in Cairo, it reopens one more time for the United States the as-yet-unsolved debate between security interests and the importance of promoting humane and legitimate governance.

The Syrian revolution at its beginning appeared to be a replay of the Egyptian one. The US pressed for a “political solution” through the United Nations, predicated on removing President Bashar al-Assad from power and establishing a coalition government. Consternation resulted when other veto-wielding members of the security council declined to endorse either this step or military measures, and when the armed opposition that ultimately appeared inside Syria had few elements that could be described as democratic, much less moderate.

By then the conflict had gone beyond the issue of Assad. The principal Syrian and regional players saw the war as not about democracy but about prevailing. They were interested in democracy only if it installed their own group; none favoured a system that did not guarantee control for its own party.

A war conducted solely to enforce human-rights norms and without concern for the geostrategic or georeligious outcome was inconceivable to the overwhelming majority of the contestants. The conflict, as they perceived it, was not between a dictator and the forces of democracy but between Syria’s contending sects and their regional backers. The war, in this view, would decide which of Syria’s major sects would succeed in dominating the others and controlling what remained of the Syrian state.

Regional powers poured arms, money and logistical support into Syria on behalf of their preferred sectarian candidates: Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states for the Sunni groups; Iran supporting Assad via Hezbollah. As the combat approached a stalemate, it turned to increasingly radical groups and tactics, fighting a war of encompassing brutality, oblivious on all sides to human rights.

The contest, meanwhile, had begun to redraw the political configuration of Syria, and perhaps of the region. The Syrian Kurds created an autonomous unit along the Turkish border that may in time merge with the Kurdish autonomous unit in Iraq. The Druze and Christian communities, fearing a repeat of the conduct of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt towards its minorities, have been reluctant to embrace regime change in Syria or have seceded into autonomous communities. The jihadist Isis set out to build a caliphate in territory seized from Syria and western Iraq, where Damascus and Baghdad proved no longer able to impose their writ.

The main parties thought themselves in a battle for survival or, in the case of some jihadist forces, a conflict presaging the apocalypse. When the US declined to tip the balance, they judged that it either had an ulterior motive that it was skilfully concealing — perhaps an ultimate deal with Iran — or was not attuned to the imperatives of the Middle East balance of power.

As America called on the world to honour aspirations to democracy and enforce the international legal ban on chemical weapons, other great powers such as Russia and China resisted by invoking the principle of non-interference.

They had viewed the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Bahrain and Syria principally through the lens of their own regional stability and the attitudes of their own restive Muslim populations. Aware that the most skilled and dedicated Sunni fighters were avowed jihadists, they were wary of an outright victory by Assad’s opponents.

With an international consensus lacking and the Syrian opposition fractured, an uprising begun on behalf of democratic values degenerated into one of the major humanitarian disasters of the young 21st century and into an imploding regional order.

A working regional or international security system might have averted, or at least contained, the catastrophe. But the perceptions of national interest proved to be too different and the costs of stabilisation too daunting.

Massive outside intervention at an early stage might have squelched the contending forces, but a long-term, substantial military presence would have been required to maintain order. In the wake of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan this was not feasible for the US, at least not alone.

An Iraqi political consensus might have halted the conflict at the Syrian border, but the sectarian impulses of the Baghdad government and its regional affiliates were in the way. Alternatively, the international community could have imposed an arms embargo on Syria and the jihadist militias. That was made impossible by the incompatible aims of the permanent members of the security council.

If order cannot be achieved by consensus or imposed by force, it will be wrought, at disastrous and dehumanising cost, from the experience of chaos.

With some historical irony, among the western democracies’ most important allies through all of these upheavals has been a country whose internal practices diverge almost completely from theirs — the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia has been a partner, at times quietly but decisively behind the scenes, in most of the major regional security endeavours since the Second World War, when it aligned itself with the allies.

This has been an association demonstrating the special character of the Westphalian state system, which has permitted such distinct societies to co-operate on shared aims through formal mechanisms, generally to their significant mutual benefit. Conversely, its strains have touched on some of the main challenges of the search for a modern world order.

Saudi Arabia is a traditional Arab-Islamic realm: both a tribal monarchy and an Islamic theocracy.

No state in the Middle East has been more torn by the Islamist upheaval and the rise of revolutionary Iran. It is divided between its formal allegiance to the Westphalian concepts that underpin its security and international recognition as a legitimate sovereign state, the religious purism that informs its history and the appeals of radical Islamism that impair its domestic cohesion.

The attempt to find security within both the Westphalian and the Islamist order worked for a time. Yet the great strategic error of the Saudi dynasty was to suppose, from roughly the 1960s until 2003, that it could support and even manipulate radical Islamism abroad without threatening its own position at home.

The outbreak of a serious, sustained al-Qaeda insurgency in the kingdom in 2003 revealed the fatal flaw in this strategy, which the dynasty jettisoned in favour of an effective counterinsurgency campaign. With the surge of jihadist currents in Iraq and Syria, the acumen displayed in this campaign may again be tested.

An upheaval in Saudi Arabia would have profound repercussions for the world economy, the future of the Muslim world and world peace. As revolutions elsewhere in the Arab world have shown, the US cannot assume that a democratic opposition is waiting in the wings to govern Saudi Arabia by principles more congenial to western sensibilities. America must distil a common understanding with a country that is the ultimate prize coveted by both the Sunni and the Shi’ite version of jihad and whose efforts, however circuitous, will be essential in fostering a constructive regional evolution.

Syria and Iraq — once beacons of nationalism for Arab countries — may prove unable to reconstitute themselves as unified sovereign states. As their warring factions seek support from affiliates across the region and beyond, their strife jeopardises the coherence of all neighbouring countries.

The conflict in Syria and Iraq and the surrounding areas has thus become the symbol of an ominous new trend: the disintegration of statehood into tribal and sectarian units, some of them cutting across existing borders, in violent conflict with one another and manipulated by competing outside factions, observing no common rules other than the law of superior force.

After revolution or regime change, without the establishment of a new authority accepted as legitimate by a decisive majority of the population, a multiplicity of disparate factions will continue to engage in open conflicts with perceived rivals for power. Portions of the state may drift into anarchy or permanent rebellion, or merge with parts of another disintegrating state. The existing central government may prove unwilling or unable to re-establish authority over border regions or non-state entities such as Hezbollah, al-Qaeda, Isis and the Taliban. This has happened in Iraq, Libya and, to a dangerous extent, Pakistan.

Some states as presently constituted may not be governable in full except through methods of rule or social cohesion that Americans reject as illegitimate. These limitations can be overcome, in some cases, through evolution towards a more liberal domestic system.

Yet where factions within a state adhere to different concepts of world order or consider themselves to be in an existential struggle for survival, American demands to call off the fight and assemble a democratic coalition government tend either to paralyse the incumbent government (as in the Shah’s Iran) or to fall on deaf ears. The Egyptian government led by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi is now heeding the lessons of its predecessor’s overthrow by tacking away from a historic American alliance in favour of greater freedom of manoeuvre.

In such conditions America has to make the decision on the basis of what achieves the best combination of security and morality, recognising that both will be imperfect.

In Iraq the dissolution of Saddam Hussein’s brutal Sunni-dominated dictatorship generated pressure less for democracy than for revenge, which the various factions sought through the consolidation of their disparate forms of religion into autonomous units in effect at war with one another.

In Libya, a vast country thinly populated and riven by sectarian divisions and feuding tribal groups — with no common history except Italian colonialism — the overthrow of the murderous dictator Colonel Muammar Gadaffi has had the practical effect of removing any semblance of national governance.

Tribes and regions have armed themselves to secure self-rule or domination via autonomous militias. A provisional government in Tripoli has gained international recognition but cannot exercise practical authority beyond city limits, if even that. Extremist groups have proliferated, propelling jihad into neighbouring states armed with weapons from Gadaffi’s arsenals.

When states are not governed in their entirety, the international or regional order also begins to disintegrate. Blank spaces denoting lawlessness come to dominate parts of the map. The collapse of a state may turn its territory into a base for terrorism, arms supply or sectarian agitation against neighbours.

Zones of non-governance or jihad now stretch across the Muslim world, affecting Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, Mali, Sudan and Somalia. When one also takes into account the agonies of central Africa — where a generations-long Congolese civil war has drawn in all neighbouring states, and conflicts in the Central African Republic and South Sudan threaten to metastasise similarly — a significant portion of the world’s territory and population is on the verge of falling out of the international state system altogether.

As this void looms, the Middle East is caught in a confrontation akin to — but broader than — Europe’s 17th-century wars of religion. Domestic and international conflicts reinforce each other. Political, sectarian, tribal, territorial, ideological and traditional national- interest disputes merge. Religion is “weaponised” in the service of geopolitical objectives; civilians are marked for extermination based on their sectarian affiliation.

Where states are able to preserve their authority, they consider their authority without limits, justified by the necessities of survival; where states disintegrate, they become fields for the contests of surrounding powers in which authority too often is achieved through total disregard for human wellbeing and dignity.

The conflict now unfolding is both religious and geopolitical. A Sunni bloc consisting of Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states and to some extent Egypt and Turkey confronts a bloc led by Shi’ite Iran, which backs Assad’s portion of Syria, Baghdad and a range of Iraqi Shi’ite groups and the militias of Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza.

The Sunni bloc supports uprisings in Syria against Assad and in Iraq against Baghdad; Iran aims for regional dominance by employing non-state actors tied to Tehran ideologically to undermine the domestic legitimacy of its regional rivals. Participants in the contests search for outside support, particularly from Russia and the US, in turn shaping relations between them.

Russia’s goals are largely strategic: at a minimum to prevent Syrian and Iraqi jihadist groups from spreading into its Muslim territories and, on the larger, global scale, to enhance its position vis-à-vis the US.

America’s quandary is that it condemns Assad on moral grounds — correctly — but the largest contingent of his opponents are al-Qaeda and more extreme groups, which the US needs to oppose strategically.

Neither Russia nor America has been able to decide whether to co-operate or to manoeuvre against the other — though events in Ukraine may resolve this ambivalence in the direction of Cold War attitudes.

Iraq is contested between multiple camps — this time Iran, the West and a variety of revanchist Sunni factions — as it has been many times in its history, with the same script played by different actors.

After America’s bitter experiences, and under conditions so inhospitable to pluralism, it is tempting to let these upheavals run their course and concentrate on dealing with the successor states. But several of the potential successors have declared America and the Westphalian world order their principal enemies.

In an era of suicide terrorism and proliferating weapons of mass destruction, the drift towards pan-regional sectarian confrontations must be deemed a threat to world stability warranting co-operative effort by all responsible powers, expressed in some acceptable definition of at least regional order.

If order cannot be established, vast areas risk being opened to anarchy and to forms of extremism that will spread organically into other regions. From this stark pattern the world awaits the distillation of a new regional order by America and other countries in a position to take a global view.

© Henry A Kissinger 2014

Extracted from World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History, to be published by Allen Lane on September 9...